What do we owe to one another? To our symbionts? This is perhaps not quite the question asked by the narrator in E.W. Harris’ new-classic, recently sonically reimagined. But it is the question I found myself asking while listening to the new version of Bad Ghost this past week.

Maybe you too have found yourself wrestling with the big existential questions these past 16 months (or past 5-10 years). There seems to be a lot of it going around. And fair enough, I think. If the crumbling of the world’s oldest continuous democracy, an ongoing, impressively disruptive – and tragically deadly – global health crisis, the never-ending displays of violent oppression – in our own country and throughout the world – all just foregrounding humanity’s slow(ish) but obstinate walk towards its own destruction doesn’t get you thinking about the big questions then, really, what would it take?

And so this was the state of my mind, I guess, and I might assume maybe yours too.

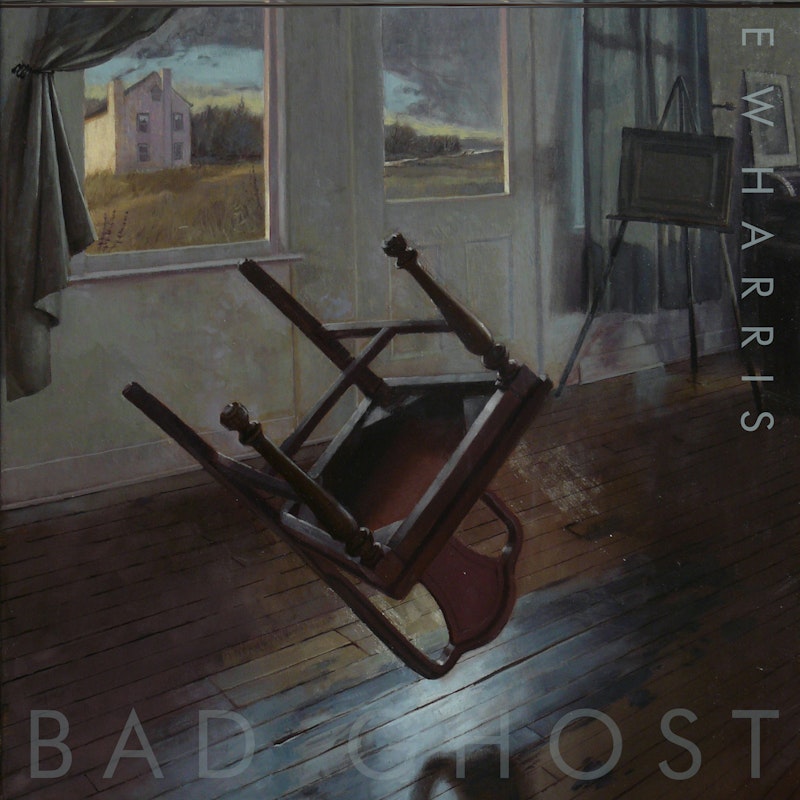

The original version of Bad Ghost, as far as I am familiar, was part of Mimetic Desire. A record I love and have also written about. It’s mostly acoustic guitar and vocals, layered and subtle. Lots going on in that seemingly simple production to appreciate and listen to again and again. Perhaps above all: a very pretty record. Cinematic in its beauty and lyrical content, even while maintaining it’s spare guitar-and-voice center mass.

The new version of Bad Ghost maintains much of the acoustic guitar-plus-vocal character while adding A LOT more in the way of production and arrangement. The song is still sung in the same high register, gossamer-like in its subtle delicacy. There is still the same insistence of propulsion, driven by that familiar right hand rhythm. And it is still a very pretty song.

This new version opens with a twinkly electric guitar pattern and some very spacey sounding reverse reverb. I’d love to see what went into creating this intro. The guitar, if it is guitar, is almost electric mandolin-like in its timbre, and the backwards tape sounds that I’m attributing to a reverse reverb may actually be from the principle recording played backwards. Or a combination? I’m not sure what alchemy is happening here, but it is very effective and lovely.

This intro bit drops off and we are immediately in the familiar sonic space of the original Bad Ghost, full of enviable and spacious reverb, while the narrator sets the stage for their own violent death on a rainy night. They were in their best red dress, you see, less like wine, more like blood.

After learning a bit about what our narrator is wearing, our sonic landscape starts to deviate from the original version. Still driven forward by the insistent upbeat of the acoustic guitar, the twinkly line from the intro reappears, answering the vocals. This rogue band is joined by a march-like snare drum and some cinematic left hand piano riffs outlining the changes. The effect is dramatic.

And, see, I know, like you probably know – cause you’re reading this – that the narrator is about to get shanked to death in the street. So, there is something about the acoustic guitar’s quick and upbeat-focused rhythm, the marchyness of the snare, the moody drama doom bells of the low piano notes, that transmit the unsettling sensation that you are not in control. You are being whisked away by a tide of forces that do not see you, do not care particularly about you, and are bringing you faster than you might like towards a violent end. Or someone’s violent end. A little like a few years before the pandemic when I used to have to transfer from the F to the 2 at 14th street during rush hour. This may sound like I’m saying I don’t like this moment in the song, but I love this. I did not at all or in any way enjoy the 14th street train transfer, and I would not want to get stabbed in the street, but I love that a piece of music is able to make me feel that urgency and outofcontrolness. Especially a song as pretty as this one.

Other musical elements start to make appearances at this point. There is some sort of synth vocal harmonizer or vocoder getting deployed. It’s great fun. It’s a bit like a chorus of retrofuturist robot singers.

I’m sorry symbiont, he says. I’ve been a bad host. I was a weak man. Now I’m a bad ghost.

And so again I ask: What does a man, bad or good, weak or strong, owe to his symbiont? Well, I suppose it depends.

The use of the symbiont, or symbiotic relationships generally, have a rich history in fiction. Let us turn to the internet experts for examples. No less celebrated a source than TV Tropes dot org points out that symbiosis comes in at least three distinct flavors:

Mutualism – This is where both the host and the symbiont (or symbiote?!) benefit from the relationship. This is like Nemo and his dad keeping their sea anemone clean while the anemone keeps them safe by zapping any would-be intruders. Or perhaps more pointedly: Like the Trill cerca Deep Space 9. Specifically, Jadzia Dax.

Commensalism – One of the parties to the (perhaps not entirely unholy) union gets a benefit from the arrangement. The other is, like, meh, it’s fine, no really, I don’t mind, it’s fine, I guess? In fiction these are often just plot devices or MacGuffins. Symbionts that magically/unselfishly provide super powers (and thus the entire plot) without so much as asking for anything in return. In the more mundane world of nature, the best I could find were things like this: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cymothoa_exigua. Which, I think we can all agree is more parasitism than commensalism. (Shudder.)

Perhaps no intimate contact is ever truly neutral in the real world?

Parasitism – There is maybe a question here as to whether parasitism is a form of symbiosis or if a parasitic relationship is a separate semantic box, different and apart. This debate is not so important for our purposes, and you know what it is. One side gets what it wants/needs. The other is actively harmed by the relationship. The parasite sucking life from the host. Sound familiar? Perhaps you have experienced this? Perhaps the United States of America recently experienced this? For four long years? Also: The Alien(s) movie franchise. (Spoiler: Weyland Yutani is the real parasite, no?)

As you may expect in science-fiction, Symbionts and Parasites are frequently used allegorically and can often be mapped onto the politics of a particular place and time. Before WWII, alien parasites made frequent appearances as thinly veiled xenophobic tropes. After WWII, as the world came to recognize the horrors perpetrated by the Nazis, there was a movement towards greater humanism, and you can see this reflected in the science fiction of the time and the influx of mutualistic symbiotic relationships between beings from different worlds. Then of course came the Cold War and a trend of parasitic aliens with distinctly Russian accents started infiltrating American fiction.

So, when I heard the re-imagined version of this song, with its classic science fiction themes, coming to us at this particularly turbulent time, I wanted to know how it mapped onto *this* challenging political environment.

E.W. has mentioned to me, and at least hinted in some of his promotion leading up to this release, that the symbiont/host relationship in this song is specifically inspired by the character Jadzia Dax from Star Trek Deep Space 9.

I had never watched DS9. I had absorbed, passively, some of the Next Generation in my childhood, and, somewhat more intentionally, watched quite a bit of the Original Series in my adolescence. DS9, though, had always seemed a bridge too far. But, given how much importance I was placing on the Symbiont in navigating what this song meant for us now in our current political struggles, AND the ready availability of DS9 episodes on Amazon Prime – a service to which I already subscribe – I saw little choice. I dove deep into Deep Space.

Let me tell you sincerely. If this song does nothing else, if it inspires you to check out this sweet, warm corner of the Star Trek universe it will have done more than its share. Honestly, what a surprising joy that was. I thought I might skip around and watch some of the more Jadzia/Trill focused episodes, but I just ended up binge watching the whole thing. Really, enjoy.

What I learned: Jadzia belongs to a humanoid species known as the Trill. A very select few of the Trill have symbionts implanted inside of them. To be paired with a symbiont is a great honor and is something you must actively work towards. There are trials, interviews, tests and only the absolute best candidates are matched and paired with a symbiont. Once paired, the host Trill gains all of the memory and knowledge that the symbiont has collected across its previous hosts, giving the host access to multiple lifetimes worth of information. The symbionts need Trill hosts to survive. So: Mutualism. In this relationship between host and symbiont, neither side is subsumed by the other. Each pairing creates a distinctly new being. Jadzia, despite some initial missteps, is eventually paired with a symbiont called Dax. The resultant pair is called Jadzia Dax.

Given the influence of this particularly marxist-humanist symbiosis – and indeed tv show, seriously, check it out – on the song at hand, I think we can immediately make some educated guesses about where Bad Ghost sits in the grand history of the sci-fi symbiont. It also opens the door to an interpretation of this song that I have come to, and will freely admit is perhaps a bit of a stretch. It will also require a lot in the way of extra-textual explanation.

But, you see, the thing is, it’s like actually the end of the world out here in the for real, and so you’ll maybe need to understand that my interpretations of art and fiction (and reality) have started to become a bit idiosyncratic and reaching as I attempt to collect them around myself like a protective balm from the darkness.

In this spirit, I suggest to you now that Bad Ghost, in both versions, is, in the grandest possible tradition, a love song.

What is love, anyway? What’s it got to do with it? (Do with it?) Is it truly just a second hand emotion? Like sci-fi symbiosis, it is a lot of sometimes conflicting things. If you are old and grown, then at some point you have likely experienced a feeling and called it love that was all-consuming, blinding, and perhaps a little dangerous. A rapturous kind of passionate love. But, again, if you are old and grown, you have also probably used this same word – ‘love’ – to describe a steadier kind of feeling, probably several kinds of steadier kinds of feelings with a variety of contexts and implications.

In Joseph Campbell’s lecture on the Mythology of Love he tells a story from the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad of The Primal Being which existed before thought or consciousness and was nameless with no knowledge of itself but then thought: “I.” And upon thinking this, the Being was aware of itself and immediately felt Fear since now realizing it was a self also realized it could be attacked and killed. Then it quickly concluded that since it was the only thing in existence its fear was unfounded. There was nothing else around that could do it any harm. But this made the Being feel a Desire for other things to be around, and it split itself into the first primal couple and they produced all of the beings of the earth. Campbell suggests that one important takeaway here is that through love we engage in this same creative act, but at the same time come together, and are better able to see beyond ourselves and past the delusion of separateness to the real truth: That we are all, in fact, one thing.

Compare this, as Campbell does, to a common interpretation of the Christian myth – that God so loved the world that they sent their son to Earth to be sacrificed for our sins. As a kind of penance, payment, or atonement for the evil of mankind.

But then another interpretation of the same myth, one more in line with the story of the Primal Being from the Upanishad – that God’s act of love in this story is not simply one of sacrifice in penance, but an act intended to bring mankind’s focus from worldly things back to God himself. So in this interpretation there is a mutual desire – Humankind’s desire for God’s grace, and God’s self-immolating desire for mankind’s respect and attention. (So: Mutualism.) Humankind’s love for God is reciprocated by God’s love for Humanity. And this love reveals the essential truth – that, in fact, they are not different, they are the same. One thing. The strange hybridity of Jesus in this myth also speaks to this. Not just Man. Not just God. Both, simultaneously.

Not unlike a certain Trill-symbiont hybrid referenced broadly in Bad Ghost. Jadzia Dax is not just the Trill Jadzia or the Dax symbiont. She is both, simultaneously.

God literally becomes human, acting out their love for humanity. The Trill seek to join with a symbiont creating one combined entity, an act of at-one-ment, as a matter of spiritual quest. As an act of love.

Love, as Roy Ayers reminds us, will bring us back together. Forever.

Let’s completely change tracks for a moment. One way to interpret Bad Ghost is as a morality play. Our hero is stabbed to death and is immediately sorry for letting down its symbiont who is now quite likely to die (or I suppose, even if it doesn’t, has to experience getting stabbed and left for dead, which it will in turn carry to its next host in a symbiotic echo of generational trauma). While the stabbing may be retribution for the picking of the antique lock in verse two, or for some other reason, the host’s confession of weakness would seem to suggest that our protagonist feels guilt and responsibility for what has happened. If this were a morality play we would expect punishment for the Host’s transgression. Certainly the stabbing may be one, but the suggestion of now having become a Bad Ghost may represent further punishment or Karmic retribution (a concept perhaps first established in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad!).

In this interpretation of the song the answers to my questions at the beginning of this review are simple and straightforward: What do we owe to one another/to our symbionts? To be strong, to be good.

This is a version of morality I recently heard echoed while rewatching an episode of Anthony Bourdain’s No Reservations set in Montana. Bourdain is sitting around an outdoor table eating game birds and organ meats and drinking wine and beer with a handful of colorful locals one of whom opines that, “we need more of John Wayne and those kind of guys that stand for something. That’s what I grew up with and they don’t have it now. The old saying is ‘Right is right even if nobody else is doing it, and wrong is wrong even if everybody’s doing it.’”

Consider another morality tale that also appears in Joseph Campbell’s discussion of love myths: Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival. After having achieved secular success through noble acts of pure and spontaneous compassion, Parzival finds himself at the home of The Fisher King, a guardian of the Grail who has been rendered impotent by a Pagan spear through the genitals. (As an aside we should note that the Grail King’s impotence affects the fertility of the land, reducing his Kingdom to a wasteland. Bad Ghost utilizes a DS9 symbiont, but is still set within the Rocket City universe. E.W. Harris fans will notice the prominent placement of such a wasteland there as well.) Parzival’s purpose at the Grail King’s castle is to heal the King’s wound in the pure and natural way of his previous successes. He is faced with a test. All he needs to do (not that he is allowed to know any of these rules) is to simply ask the King about what happened to his dick/balls and all will be healed and made right and Parzival will be crowned New King of the Holy Grail. However, Parzival has been told by a knightly mentor that it is inappropriate for a knight to be too curious. And so, upon meeting the King, despite his natural inclination to ask about the bit of pagan spear hanging from the Fisher King’s groin, he heeds the words of his mentor and keeps it zipped. Because he is concerned with his image, he doesn’t follow his natural inclination, and as a result he is humiliated and banished from the Grail Castle and spends the next several years cursing God and wandering around the woods learning life lessons from forest hermits. Eventually, after much wandering, striving, cursing and learning, he gets a crack at another spiritual test, this time in the form of a Muslim brother (literally) from another mother, the two of whom, after fighting and trying to kill one another, make friends, realize they actually have the same father, and thus pass the test and are both welcomed back to the Grail Castle and made rulers of their respective kingdoms.

They recognize their true unity through the disguise of their apparent differentness. Which should sound like a familiar theme at this point. (This from a poem written in 1210, in Europe, during the crusades. (!))

How frustrating! And how are you supposed to know what to do anyway? Didn’t Parzifal just get lucky at the end? I mean, he tried to do the right thing the first time. A stand up dude, who probably looked a lot like a medieval John Wayne, told him not to ask too many questions, just be cool. You know, like John Wayne. So that’s what he did and for that he gets banished to the wilderness? In the end he actually tries to murder his half brother in battle, but his sword breaks on his bro’s helmet. For that he gets the Grail? Wayne himself was a supporter of Joseph McCarthy, a black-list enforcer, a member of the John Birch society, voted for Nixon. All positions that I imagine he thought were noble and honorable, even as they actively disenfranchised and marginalized people for their beliefs. Beliefs that included things like, you know, a communal connection between all people. So it’s one thing to pound the table and suggest we need people to stand for something, but the details of just what that something is seem to matter. I might pick the antique lock on the laboratory door too. Maybe it seemed important at the time. Maybe it seemed like a noble risk given the circumstances. Who’s to say what’s right?

But what if we zoom way out. Let’s take a common theme at face value for a moment. What if we are all one thing. Whether that thing is bits of a primordial being, or God, or cosmic dust, or energy, or some combinatorial substance we don’t have proper knowledge of or words for. What if we also accept that love, in all its weird, seemingly contradictory forms, does actually serve to get us closer to this truth about the nature of this connection. Maybe further, that it is this pattern of love and truth and connection that forms a kind of collective praxis. Even further, that this praxis is somehow necessary to our collective survival. Perhaps the reason that poems, songs, novels, tv shows, spiritual texts, mystic documents, 60’s era Joseph Campbell lectures, and the primary doctrines of major religions all contain similar themes that add up to we are all one, love one another and you will understand the truth, is that these are the messages we need to continually send to future generations if we are going to find a way to survive. The Fisher King was impotent and his lands lost their fertility. In Eschenbach’s telling, the King represents the fact that the Church had become an oppressive, divisive force. They acted in contradiction to their own teachings of love and connection, losing the ability to spread the message to future generations, and the result was a wasteland.

Maybe part of the solution is not to get so caught up on the details after all. I still need to see the details, and talk about the details. But I can’t let them capture me in a prison of my own construction. I need to be able to intellectualize that John Wayne was a dick. I need to be able to say: “John Wayne was a dick”, but I need to be able to say it while loving John Wayne as a part of the greater mass of things to which I am a part. And ideally, I’d like to be able to say it without getting shanked in the street in a red dress in Montana. I don’t need to believe in an afterlife, heaven, hell, reincarnation, or the existence of Dax-like symbionts to believe that the symbolism of all of these things could be useful in defining such a praxis.

And the reason for this is that we are all of us engaged in a complicated form of symbiosis with one another. Not only with everyone currently existing, but with everyone who has ever existed and will ever exist. That unifying combinatorial substance I talked about earlier could simply be the history and future of humanity at large. The details of whether the new people now passing through are cheap Hollywood sequels of original properties or a new wave of souls on their way to an increasingly crowded afterlife aren’t actually that important. People did things a long time ago that have consequences now, and these will echo and reverberate long after we are gone. The long shadow of the bad ghost, or the giant’s shoulders that propel us to greater heights, either way, there is an impact. Some impacts are big, some ripple more subtly, but they all add up. And our very survival depends on the outcome of that calculus.

The symbiosis in Bad Ghost, like the symbiosis in DS9 represents this connectedness between all of us throughout time. Much the same as a God choosing to be born and to die as a human being symbolizes the connectedness of all things. The Host in Bad Ghost is stabbed to death in the street because of their own choices and weaknesses, but also because of the choice of the assailant to stab them. Such is the seeming arbitrariness of our existence. The sword breaks on your brother’s helmet, and he makes a choice not to stab an unarmed man, and you are both rewarded. In a perfect world, a world where all of humanity comes to realize its connection, perhaps, as in Parzival, this stabbing does not occur. Perhaps scenarios where the picking of locks on laboratory doors is a temptation also do not occur. We do not need to live, though, in a perfect world in order to survive. But we do need to work collectively towards a praxis of stating our truths while simultaneously holding our connection with one another in the front of our minds. And we will be tested regularly in our ability to do this and we will fail. Because it is very hard. And so the statement of the chorus, the dispassionate I’m sorry symbiont, I’ve been a bad host, is the calm judgement of such a failure. The Host on this day or perhaps in this lifetime did not live up to their duties to their symbiont – namely: the rest of human existence. But the Host’s failure is not determinative, the collective praxis must continue. And the way we strengthen our abilities for the next test, whether that test comes in the form of a laboratory door, an enemy knight, some guy in Montana talking about John Wayne, questions about your worthiness to host a symbiont or your next Thanksgiving meal is through the practice of the rituals of love. One such practice? The sincere apology. I’m sorry symbiont. And so Bad Ghost exists for me in this grand tradition of messages of love that we must continue to create and pass along for our future generations. It is a love song.

So what, again, do we owe to each other? To our symbionts? The same thing that we owe to ourselves. Because, ultimately, these are all one thing. Love.

Also, there’s this whole bonkers proggy/stadium rock section in the middle. It’s a brilliant and enjoyable record. Very nice work E.W. and Hanging Dilettante Records. Check it out: https://ewharris.bandcamp.com/